Raqib Shaw

Jorge’s in the front room, crashed out on the day bed and I’m here in the bedroom, in my dressing gown, staring at my laptop, thinking, ‘Maybe I should write something.’ So…I want to write about a recent event that made a big impression on me; Raqib Shaw’s largest solo exhibition to date, La Nuit d’Amour, that took place on Valentine’s night at the Manchester Art Gallery.

We’d been invited to the private view by Raqib. But because we hadn’t seen him for a few years we weren’t sure, given his prominence in the art world now, whether we’d get a chance to speak to him. We needn’t have worried. Within minutes of arriving at the upper floor gallery he came bounding over. ‘Clayton you bitch. You haven’t aged a bit!’ ‘Congratulations!’ I gushed. ‘What for?’ he replied. ‘This!’ I said, gesturing toward the work. He looked slightly offended. ‘This is nothing.’ He wasn’t being modest. He meant it (and I immediately felt put in my place).

Raqib is unique. He has described himself as merely a vessel, channeling the work. The success that comes with it means little (and this from someone whose first work, The Garden of Earthly Delights II, sold for $5.5 million at Sotheby’s in New York when he was just 33). It’s what makes him such a rarity. In this mass communication/social media age, where the emphasis is on showing the world what you can do, what you’ve achieved, how popular you are, where your place is in society, Raqib has set himself apart. He is a recluse. He doesn’t do email, phone calls and rarely ventures outside his studio. All he does is paint. All day. Every day. Never taking a holiday. To even leave his studio and come to his own show is extremely rare. But here he was. Just as eccentrically camp and loveable as when he first stepped into our Soho shop all those years ago.

For the 30 odd guests, (friends, dealers, gallery owners) the evening started with Sir Norman Rosenthal giving a speech. This was followed by a sextet playing the Rites of Spring, followed by bottle after bottle of champagne, then more speeches, the viewing, and then an Indian buffet. God knows how much Raqib must’ve spent because once the main doors opened at 6pm, and a few hundred people poured in, the champagne continued to flow. Even the railings around the museum were decorated with vines, tree bark and spring bulbs so that the exterior of the gallery will be in full bloom for the duration of the show (the idea being to reproduce the interior of his studio and invite the public into his magical world).

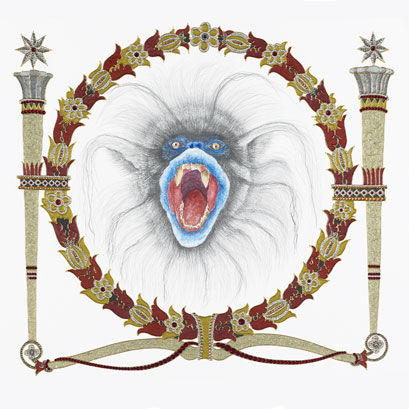

But what of the art? It’s such a difficult thing to explain (and I know, because I’ve tried). But I’m guessing that seeing Raqib’s work must be provoking the kind of reaction that Francis Bacon’s did when first viewed (Bacon was working at a time when abstraction was the standard by which art was being judged). There are so many different readings. It’s been described as a collection of dark and violent images inspired by ancient myths and religious tales from both East and Western tradition. A blend of Kashmiri textiles and Japanese lacquered screens. There are flowers, butterflies, humans with animal heads (after all, we’re all animals), each bird, fish, monkey, tree, carefully filled in with enamel-like paint, before being covered with rubies and emeralds and other precious stones. As a comparison (and it’s hard to draw one), I’ve always viewed Raqib’s work as a ‘Hieronymus Bosch for the 21st Century’. You have to see this work in person to appreciate the dazzlingly beauty. It just doesn’t come across online.

But what does it mean? I remember standing in front of one of his paintings a few years ago and asking him the same thing. He said, ‘Claytee, you wrote about what you’ve been through. Well this is what I’ve been through.’

There is a genius living amongst us in London and we’re very lucky to have him.